The right to choose one’s spouse is a fundamental human right, a women’s right as well as a man’s. Yet, for many years, women have been denied this right and forced into marriages without their consent.

This practice not only violates their human rights but also perpetuates gender inequality and undermines the principles of freedom, autonomy, and human dignity.

In many parts of the world, women are still subjected to forced marriages, child marriages, and other forms of arranged marriages that deprive them of the right to choose their spouses.

Women’s Right to Choose Their Spouse

In some cases, women are forced to marry against their will due to cultural or religious beliefs, economic circumstances, or family pressures.

This practice is not only a violation of their rights but also exposes them to numerous risks such as domestic violence, sexual abuse, and reproductive health problems.

The right to choose one’s spouse is enshrined in international human rights laws and treaties such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

These treaties recognize the right to marry and found a family as a fundamental human right and prohibit any form of coercion, discrimination, or violence in the context of marriage.

Women’s right to choose their spouses is essential for achieving gender equality and empowering women. When women have the freedom to choose their partners, they are more likely to enter into relationships based on mutual respect, love, and consent.

This, in turn, contributes to healthier and more fulfilling relationships, improved mental and physical health, and greater social and economic opportunities.

Justice Mussarat Hilali to Become First Female Peshawar High Court Chief

Moreover, when women have the right to choose their spouses, they are more likely to exercise their other rights, such as education, employment, and political participation. This not only benefits women but also contributes to the overall development and progress of society.

To ensure that women’s right to choose their spouses is respected and protected, governments and other stakeholders must take concrete steps to eliminate forced marriages, child marriages, and other forms of arranged marriages.

This includes strengthening laws and policies that protect women’s right, increasing access to education and economic opportunities, and raising awareness about the harmful effects of forced marriages.

The Unforgettable Tale of Saima & Arshad

In the spring of 1996, the news was brimming with tales of love. When Saima Waheed was a 20-year-old MBA student, she crossed paths with 27-year-old Arshad Ahmed.

Arshad was a tutor for Saima’s younger brother, and he visited their family home twice a week in the upscale neighbourhood of Model Town in Lahore. Despite seeing Arshad at the house, Saima had never met or spoken to him before.

Arshad worked as a lecturer at Pattoki Government College, earning a modest salary of 5,000 rupees ($17.75) per month. According to reports, Arshad’s father had a prior acquaintance with Ropri, Saima’s father, as they both worked in the same market in Lahore over a decade ago.

Saima, on the other hand, was the head girl at Lahore College for Women and a member of the debate team. Her father, Abdul Waheed Ropri, doted on her, providing her with a generous monthly allowance of 10,000 rupees (equivalent to $35.50 today) for both her expenses and her work at his pipeline manufacturing company. She had access to a mobile phone, credit cards, and a personal driver and car.

Saima and Arshad’s paths first crossed at a debate competition, after which they began talking on the phone. When Saima turned 21, Arshad proposed marriage, and his parents went to Saima’s home to seek her hand. However, Ropri had already arranged for Saima to marry her cousin when she was just 14 years old, but she refused to wear his ring and the engagement was called off. Later, her father accepted a proposal from a doctor who Saima had only met once at their engagement celebration, and who was 41 years old at the time. Saima realized she was in love with Arshad and begged the doctor to withdraw his proposal, but he refused.

Saima refused to be treated like a commodity to be sold to the highest bidder, as she expressed in an interview. In February 1996, she deceived her parents by claiming to collect some certificates from college and secretly met Arshad at a lawyer’s office where they signed a marriage contract called “nikkah.”

Just over a week later, Saima informed her parents about the marriage, which resulted in her father hitting her across the face – the first time he had ever laid a hand on her for exercising women’s rights.

Saima was confined to her room without food for three days. Her father took away her mobile phone, car keys, and money, and cut off her telephone line. Saima’s father even threatened to go ahead with her marriage to the doctor despite her objections.

Actor Amna Malik’s Upcoming Drama Will Tackle Child Marriage

However, Saima refused to sign the marriage certificate and told her father that she would not marry anyone else, even if it meant sacrificing her life plans.

A month later, Saima took advantage of an unlocked door and escaped by climbing over the boundary wall of her family’s home. She then took a taxi to the office of Asma Jehangir, a human rights lawyer whose name she had seen in the newspapers and on posters around her college campus.

In interviews, Saima has given varying accounts of how she found her way to Jehangir’s office, but she eventually climbed two flights of stairs above a bank to a plywood door.

Dastak

In 1996, Robina Shaheen had been in charge of the Dastak women’s shelter, started by Asma Jehangir’s sister, the lawyer Hina Jilani. The shelter’s name, “Dastak” means “a knock at the door”.

When Robina met Saima in April 1996, she noticed that the girl appeared confident despite being fearful. Most women who came to see Robina were anxious and had trembling hands when trying to speak. Some of them spread their hands before her as if asking for help. Saima confided in Robina that she had escaped her home and was afraid for her life.

Less than two weeks after arriving at Dastak, Saima’s father filed a petition to declare her marriage void, claiming that she did not seek his permission for it. The court hearing focused on various religious, social, and cultural arguments. During her stay at Dastak, Saima spent her time reading newspapers and giving interviews over the phone. She made friends with the staff and enjoyed eating a dish called “gaaj maaj.”

One day, Saima’s male family members walked into the AGHS office where she was staying. They had successfully petitioned the court to move Saima to a government-run women’s shelter, claiming that she was under an “evil” influence at Dastak. However, Saima refused to go with them, fearing that they would take her home forcibly.

In the ensuing struggle, Saima was dragged by the hair by her father, and the police intervened to take her to a station. In court, Jehangir argued that Saima, as an adult, had the right (women’s right) to choose where she sought shelter. Saima expressed her desire not to go to a government shelter or her parents’ home.

After spending five days at a government shelter, the judge allowed her to return to Dastak. Saima’s story illustrates the struggles that women in Pakistan face when attempting to assert their independence and choose their paths.

The Blame Games

In 1996, Justice Abdul Hafeez Cheema passed a verdict on two cases which would later have implications for Saima’s case, six months after her father had petitioned the courts to nullify her marriage. Justice Cheema declared the marriages of two girls invalid as they had married without the consent of their male guardian or “wali”.

One of the lawyers for the parents argued that if every girl was allowed to run away, many would fall victim to manipulative people in an Islamic society.

In his judgement, Justice Cheema attributed a decline in moral values to TV shows: “After the introduction of dish antennae and… [TV stations] not merely containing obscenity but targeting to destroy the Islamic concept of life, one cannot close one’s eyes over the increasing cases of abduction, rape and secret courtships.” He claimed that the country was witnessing a “tornado of sexual rebellion.”

![[Courtesy: Sanam Maher]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/s4.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C513&quality=80)

This ruling set a dangerous precedent as it meant that the girls could be prosecuted under the Hudood Ordinances.

On the day of Prophet Muhammad’s birth in February 1979, military ruler Zia ul-Haq declared the new “zina” laws to “Islamise” Pakistan.

These laws made sex outside marriage illegal and punishable by lashes, stoning, or incarceration. Rape was now defined as intercourse between two persons who were not married or sex with consent granted based on the incorrect belief that the two persons were married.

The new laws caused concern among women who had married without their parents’ or “wali’s” consent. Women’s rights activists were alarmed by the laws that prevented women from making independent decisions about their personal lives. Despite having a female prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, women were still restricted in their decision-making abilities.

In January 1997, a survey conducted by the magazine Herald revealed that 66% of men and women would not allow their daughters to marry of their own free will. Some women belonging to religious organizations held a demonstration outside the Lahore High Court in support of Justice Cheema’s verdict.

The Herald survey indicated the dangerous precedent set by the verdict, as it encouraged the prosecution of girls under the Hudood Ordinances. “Are love marriages better than arranged marriages?” Eighty-seven per cent said, “No.”

Federal Shariat Court Announces Verdict Regarding Child Marriage in Pakistan

Ray of Sunshine for Women’s Right

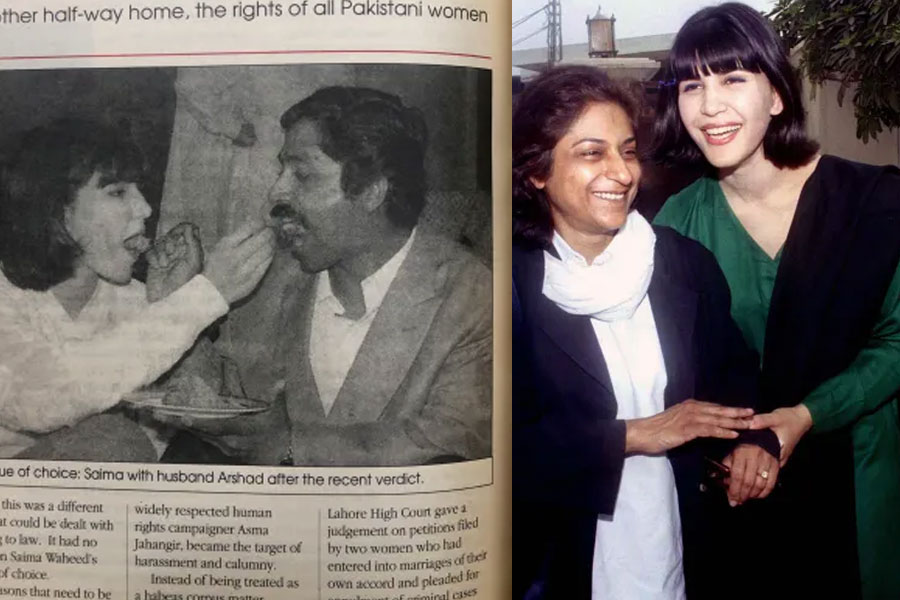

In March 1997, two of the three judges ruled that Saima and Arshad’s marriage was valid and that a Muslim woman who is an adult can choose her husband without seeking her guardian’s approval.

Dastak celebrated with sweets, and Saima waited eagerly to meet Arshad, who she had not seen in months. Arshad had been arrested in May 1996 and accused of forging the marriage certificate.

When he was released, a judge ordered that the couple should not meet until their case was closed. Saima told reporters that she felt “like the first drop of rain,” and both Saima and Arshad expressed a desire to write a book about their experience.

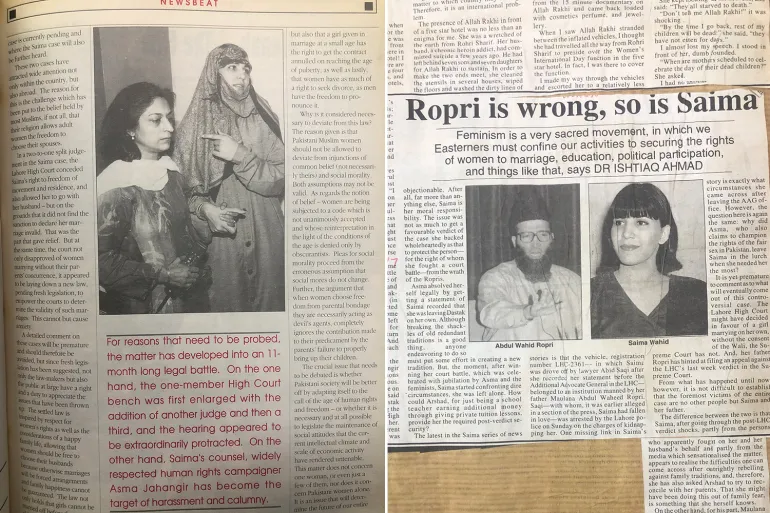

Asma Jehangir said, “We got by with the skin of our teeth. Women may have won the battle, but the war is not yet won.” The verdict did not fully support women.

Justice Malik Muhammad Qayyum’s judgment validated the marriage, but he could not find a principle on which to argue that an independent, adult Muslim woman could not marry of her own will. However, he stated that “run-away marriages are abhorrent and against the norms of our society.”

Justice Khalilur Rehman Ramday, who also found in Saima’s favour, called for legislation to make “immoral relationships and secret marriages a penal offence.”

He was dismissive of the idea of women choosing their husbands and referred to it as “husband shopping.” He also stated that “females should ordinarily stay indoors,” and if they have to speak with a man, they should do so from behind a screen or a veil.

Justice Ihsanul Haq Chaudhry dissented from the majority opinion, stating that if women marry without their wali’s consent, “Marriage will lose all its sanctity and the witnesses, lawyers would all be hired/arranged… as is happening in Reno, Nevada.”

Abdul Waheed Ropri, Saima’s father, expressed his humiliation and pledged to appeal the decision in the Supreme Court. However, in 2003, the Court ruled against him again. By then, Saima and Arshad had moved to Norway.

Where is Saima?

It has been 27 years since the case, and unfortunately, no one knows where Saima is today. Asma Jehangir, who played a crucial role in the case, passed away in 2018. Robina, who had spoken to Saima during the court case, remembers her as an enthusiastic and determined individual, who firmly believed in her cause.

Despite Saima’s photo holding Jehangir’s hand tightly and gesturing passionately, no one at AGHS or Dastak has heard from her since March 1997, not even a message of condolence when Jehangir passed away. They believe that Saima deliberately wants to stay hidden, and no one has been able to track her down.

Many women today are not aware of Saima’s story, and Nida, the lawyer at AGHS, explains that most women only see a nikkahnama on the day they get married and do not know about their rights to choose whom they marry. Young women are not taught about Saima’s case, which is a significant part of women’s right history all women should know.

What are your thoughts? Share them with us in the comments below.

Stay tuned to WOW360.